A Photo Essay by Hannah Fixson

Over in Anacostia, a 45 minute ride on the metro from Tenleytown-AU, the children of Horton’s Kids are growing up in a changing community, very different from the one found here in NW DC. Between gentrification, historic discrimination and high crime rates, there is pain and beauty, and the fight for justice and liberation.

This story begins on our side of the river. Panera, next to a Target, next to a Five Guys, next to a Whole Foods. It goes on and on. The food desert that awaits in Anacostia dreams of the abundance found at the Tenleytown-AU metro station.

On the train you start to see the colors shift. Red line to green line, white university students, black working class people. It’s a change that’s hard to miss when you step off the green line in Anacostia and feel like you are a million miles away in the same city.

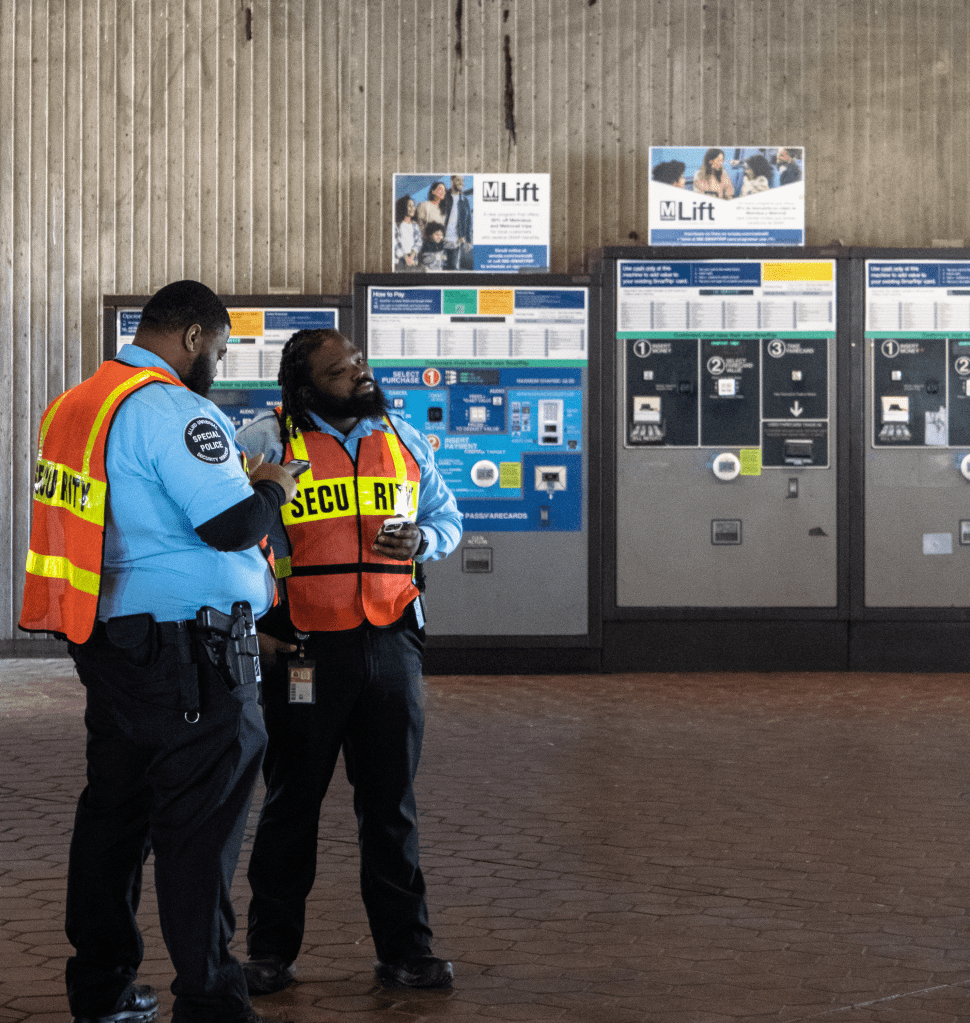

Getting off the train in Anacostia, the heady air of police presence is palpable and unavoidably different from the environment we started in. Outside of the train station an ambulance sits, ready.

The streets are filled with watchful eyes, people moving about their day and me, an anomaly among them. Fliers posted tell stories of justice and community.

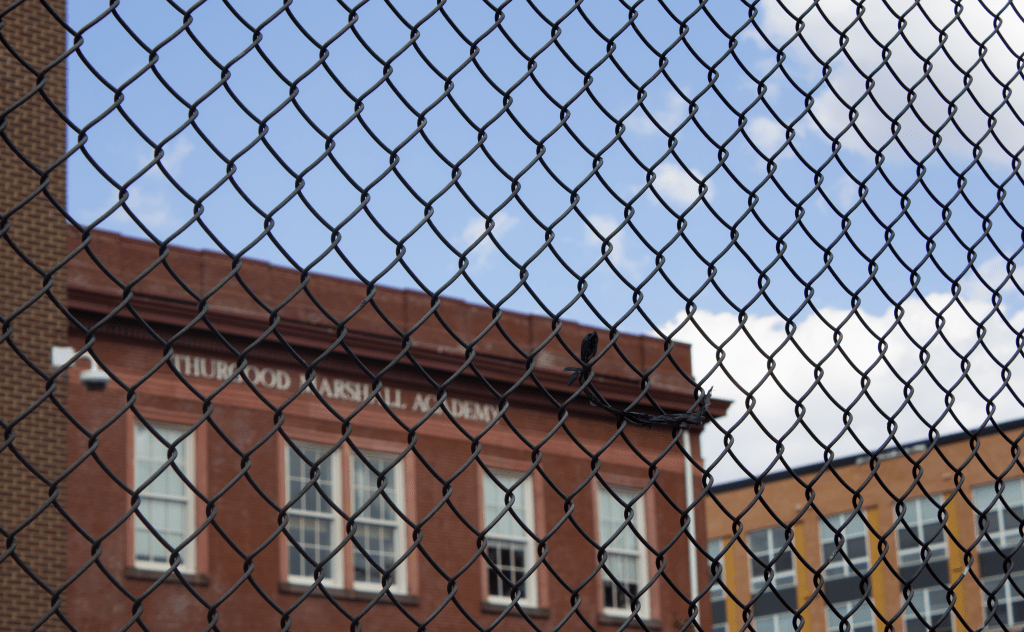

Everything is fenced in. The schools of the kids that slowly make their way to Horton’s Kids after inevitably stopping at the corner store for some corn snack brimming with red-40.

The fences feel separating. Even still, the kids are laughing, Takis in hand.

Every few squares of sidewalk are marked by piles of trash. “No Littering” and “Drug Free Zone” signs seem to have little effect on the soda cans, plastic water bottles, fast-food wrappers, cigarette butts and everything in between.

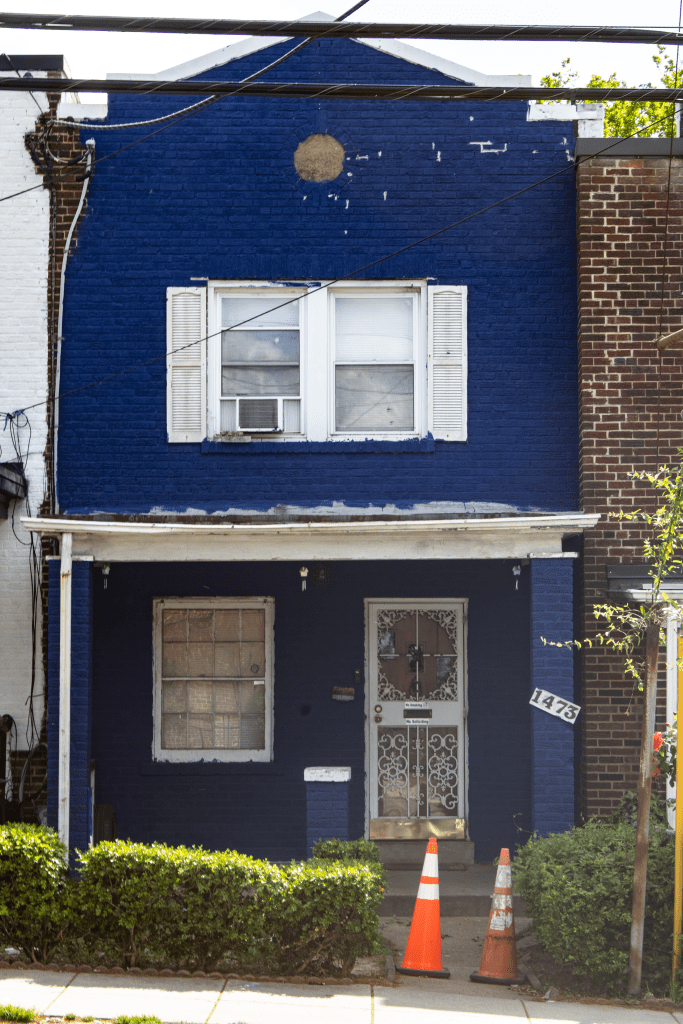

Colorful murals and older brick buildings stand determined next to gentrified monotone paneled buildings that are jumping up out of thin air. The juxtaposition of art and history against new, lifeless apartment buildings is the expression of a community fighting for its right to remain where it has against all odds. Gentrification has continued to drive Black communities out of their historical neighborhoods (Fenston, Turner, 2018). This might eventually be Anacostia’s fate but the art and music that floods out of the streets keeps the fight alive.

Old, worn signs are tired of reminding people that they should report crime and keep a watchful eye. The street is as it always has been.

And there is beauty. Vibrant houses with flowers out front and voices ringing out from inside. The reality is that this community lives, despite everything. The children grow up knowing both sides of this story.

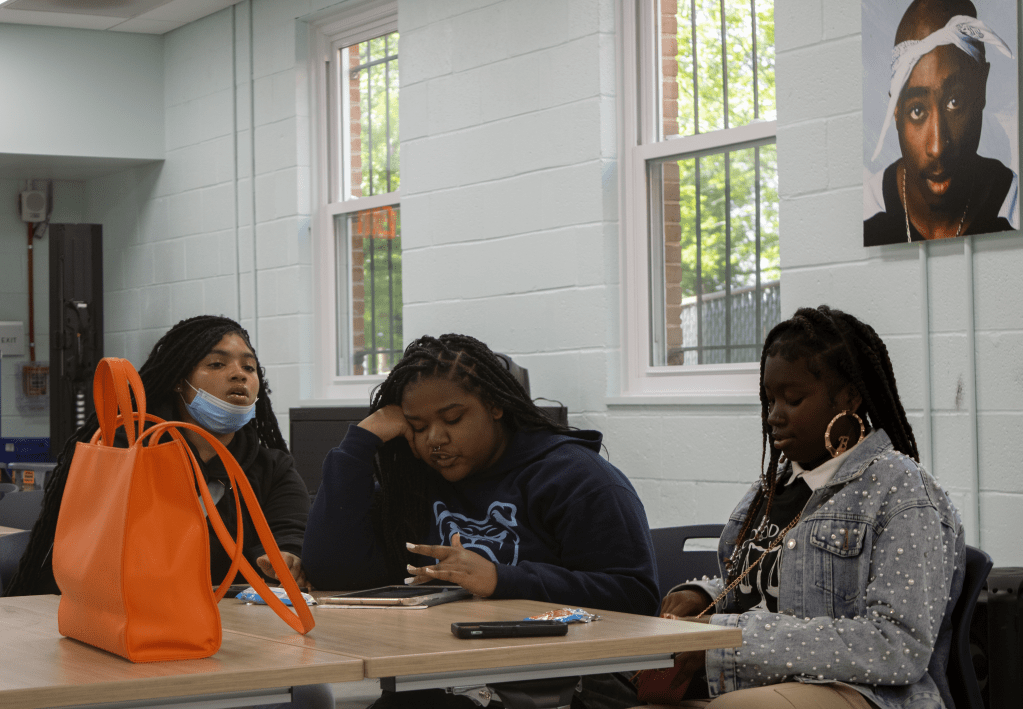

Once inside Hortons Kids, it sings of black power and excellence.

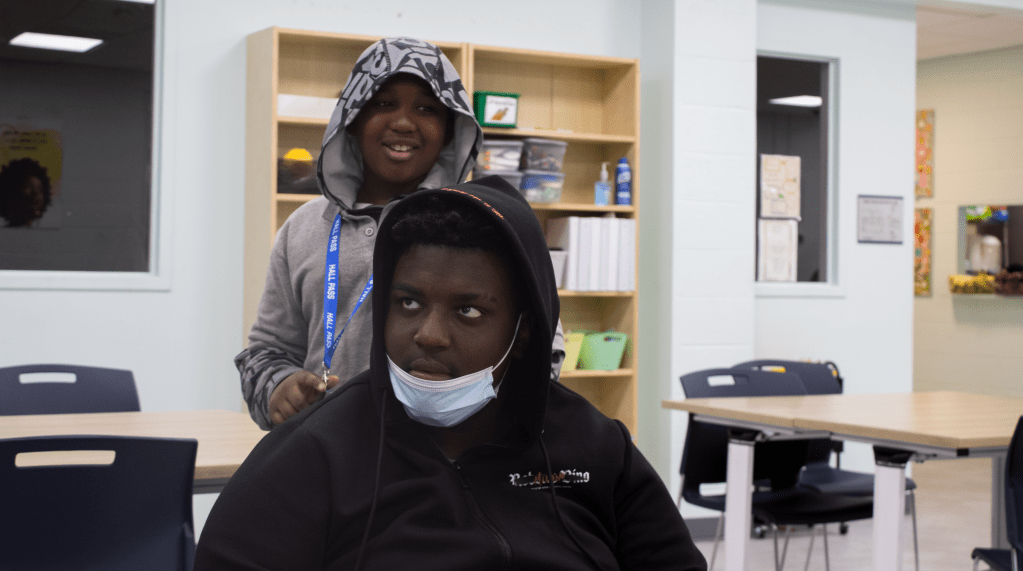

The kids laugh and talk about everything other than what they’re supposed to. The world outside is hardly forgotten but in here it can seem far away.

Art and color paint pictures of justice and liberation. The kids don’t always note them, but maybe somewhere, deep down they remember.

When asked about violence in the community, suddenly everyone has a story. They all understand that pain.

Kids see everything. They seem to know everything about their community, even if they don’t talk about it.

I was a stranger to Horton’s Kids. “I was new, and white, and from out of town” (Ramsey 2014). But in the end I was a kid not so long ago, and in the end what kids want is to be understood.

Works Cited:

Ramsey, David. “I Will Forever Remain Faithful.” Oxford American, 19 Mar. 2014, oxfordamerican.org/magazine/issue-62-fall-2008/i-will-forever-remain-faithful.

Turner, Tyrone, & Fenston, Jacob. “Anacostia Rising.” WAMU, 26 Mar. 2018,

projects.wamu.org/anacostia-rising/.